Creativity and Clichés

Abstract

Art is a sensitive subject in both academic institutions and home fronts because of negative assumptions based on clichés and stereotypes. These biased ideas create contemporary issues in art education classroom settings and negative dialogues between parents and students over their future. It is important to dispel these trite and misconstrued concepts by introducing positive examples of professional workers in the art industry, elevating artists as multifaceted creators, and offer ways to become a successful and imaginative professional with several sources of income to support their creative life.

Keywords: clichés, stereotypes, art education, starving, successful, creative, multifaceted

Creativity and Clichés

Clichés are preconceived notions that often color one’s perception, values, expectations, and decisions. In many instances, these clichés can often lead to a negative dialogue within ourselves about things we know either nothing or little about. The most common stereotype about creative types is the trite image of the “starving artist”, which portrays art as an unstable way to support oneself instead of celebrating itas a robust resource to earn income. Moreover, it is treated as a phenomenon that only the select few may witness financial stability and recognition. Unfortunately, these misconstrued beliefs influence academic institutions and families’ ideas about art and art education. Some academic administrators do not see art as a subject worthy exploring and investing additional funds into other than viewing it as a “special” class in the modern K-12 schools. Many parents discourage their children from becoming artists because of the fear that they will not be able to support themselves. Students become less engaged and art educators are faced with another obstacle to overcome in the art classroom. Additionally, these misguided concepts ignore the symbiotic relationship between art and other subjects, particularly business. Artists and entrepreneurs have common traits of creativity, problem solving, risk-taking, and innovation. Ironically, these are the same qualities future employers are seeking in the workforce pool. According to Reilly (2018), “a 2016 report by the World Economic Forum predicted that the top three job skills in 2020 will be complex problem-solving, critical thinking and creativity” (p.84). Art requires all three skills from artists. Therefore, it is critical to help other people make positive mental connections to help break these stereotypes. This paper will focus on dispelling the contemporary issues and clichés by understanding the risks and gains of being an art maker and entrepreneur, exploring ways to encourage students to achieve their goals in leading a creative life, discovering approaches to be a successful artist with viable sources of income flow and redefining what a “traditional” artist looks like.

Mentors and Mentees

There is a long history of artists who have witnessed blights and triumphs in the art industry. By reviewing creative predecessors, one can learn to circumvent the pitfalls and understand how to emulate prosperous strategies to gain employment and success. For example, Jean-Honoré Fragonard was an artist who witnessed much success during the Rococo period, but he became poor after refusing to acclimate when Neo-classical styles replaced it. El Greco was very pompous, and did not have many patrons during his living years. However, he achieved popularity after his death due to his unique techniques that combined attributes of Mannerism, “Titian’s use of color and Tintoretto’s lighting” (Strickland, 2017, p. 45). Likewise, Johannes Vermeer did not receive recognition until after his life ended. He suffered from impoverishment due to war and a collapsed Dutch-economy. Another example, Claude Monet exhibited difficulties in balancing his finances due to the exorbitant debts for a lavish lifestyle he led during the earlier phase of his life when much of his work did not sell. Eventually, he regained his financial bearings when his artwork became popular during the latter part of his life. These artists struggled or passed away poor due to the inability to adapt to changes in the industry, a bad reputation amongst patrons and art critics, economics and hostilities, and mismanagement of money. These downfalls and risks are realistic financial obstacles anyone can encounter and is not only associated with artists and entrepreneurs. Some instances are uncontrollable and others are manageable. Thus, one can always reinvent oneself to stay current with trends, cultivate their brand respectably with solid work ethics, and properly manage their assets.

Every industry has its negatives and art is no different. Nonetheless, there are numerous successful artists in today’s market to reference. For instance, Thomas Kinkadecreated his empire and secured wealth through marketing strategies, and incorporated technological innovation of mass reproducing his paintings. He dubbed himself as the “Painter of Light”, trademarked it, built franchises of galleries dedicated to his artwork, licensed out rights to use his imagery, and created a foundation dedicated to charity. Lisa Solomon, a mixed media artist and photographer, networked with her professors after graduation from The University of California at Berkley to help gain employment at galleries. Also, she acquires revenue from published art books and monographs of her work. In an interview, she recommends maintaining contact with colleagues and professors, maintaining a solid work ethic, and facing fears to further one’s career (Congdon, 2014, p.24). Olivia Be’Nguyen is a self-taught artist who has amassed a large audience of followers on several social media platforms to promote her distinct style, artwork, and her message of positivity. She gained recognition from developing massive paintings of musical artists such as Drake, Big Sean and Rick Ross. Camilla d’Errico is a working professional who earns a living by showcasing in international galleries, teaching classes, selling artwork at major events like Dragoncon and Calgary Expo, and publishing books for artists to learn her techniques or for adults to color. In today’s world, artists are no longer bound to solely rely on gallery sales to earn a living. These accomplished art experts enjoy prosperity and recognition through technology, networking, marketing, self-promotion on social media, and generating several streams of income.

Artists and Entrepreneurs

The beauty of choosing to live a creative life is the unexpected surprises, and crafting a living like any other masterpiece. It takes a high level of willingness to step out on faith, affinity for risk-taking, divergent thinking, mental endurance, and being completely honesty with oneself to go through the process. Societal norms and expectations can be limiting such like working a monotonous job with the same hours and pay, with little-to-no room for flexibility or advancement. It can be a complete shock to make the change from a nine-to-five shift to a self-made schedule, or switching from a standard direct deposit check to managing invoices and making deposits. Artists and entrepreneurs are synonymous with daredevils (a healthy stereotype in this case) because they define their own limits, rules, and indicators of success. Cameron (2002) suggests the following:

In order for us to grow as artists, we must be willing to risk. We must try to do something more and larger than what we have done before. We cannot continue indefinitely to replicate the successes of our past. Great careers are characterized by great risks (p. 73).

Therefore, success starts with one’s mindset, which affects the ability to adapt and prepare for any possibility. Casnocha and Hoffman (2012) describes the mode of operating in “permanent beta” as an influx state of constant testing and adjusting business systems such as rolling out new programs or policies until it is perfected. This tension keeps a person in a state of readiness, and increases their ability to evolve professionally within a market. An additional tool Casnocha and Hoffman (2012) proposes is a coined-term called ABZ Planning, which defines Plan A as the present job, Plan B are opportunities to maximize by pivoting, and Plan Z is the back-up plan for if and when the business fails (p.58). Therefore, an entrepreneur must stay two steps ahead of themselves and their competition.

Resources

Artists and entrepreneurs, regardless of their level of expertise, should have a basic understanding of their own identity, and develop skills in scheduling, creating business plans, marketing, logistics and managing venues. Congdon (2014) provides an all-in-one tool kit as a foundational springboard for starting a career as an artist by delving into the do’s and don’t of the art industry. Like Casnocha and Huffman (2012), Congdon reiterates the importance of mindset, creating an inner mantra of positive affirmations as an artist, and dedicating studio time as a source of deep meditation. The author’s book demonstrates how to self promote via press kits, social media, email blasts and owning a website domain in the artist’s name. Congdon introduces several ways to generate revenue through illustrations, licensing (the same tactic employed by Kinkade), printing gicleés and publishing books of one’s artworks, teaching and hosting workshops. Also, she provides tips on pricing, shipping artwork, negotiating contracts for commissions, applying for residencies, and preparing to show in galleries and exhibitions. Congdon provides extensive tips and resources on how to start up an artistic enterprise, however, it is Freeman-Zachery (2007) who helps put a creative spin on drumming up attention from gallery representation and introduces playful segments to stimulate the artist’s creativity. Similar to Congdon (2014), Freeman-Zachery (2007) attributes much success to marketing. Yet, this Freeman-Zachery incorporates the imaginative and innovative side of business through the eyes of artists. Freeman- Zachery (2007) interviewed James Michael, a found-object sculptor, who discussed creating distressed mail with older postage stamps to pique gallery owners’ interest into opening the package to view his slides. Michael said, “This little trick worked like a charm and got my foot in the door with many galleries that might not otherwise have ever agreed to view my slides” (Freeman-Zackery, 2007, p. 130).

Another concern most artists face between creating masterpieces and building a business is pricing their artwork. It is similar to a balancing act on a tight rope between the market, and the value an artist puts on their exerted energy, intellectual property, and physical work for each art piece. Congdon (2014) and Towse (1996) believe the market is a focal point that influences pricing. However, Congdon views the concept of pricing from a methodical and ethical standpoint, whereas, Towse’s perspective focuses on the labor and time, economics and legalities. Although the approaches differ, both give a well-rounded foundation for artists to begin with estimating and valuing their work. “Familiarize yourself with what other artists are creating, how their work is priced, and whether it’s selling, and you’ll be better prepared to price your art to sell” (Congdon, 2014, p. 97). Additionally, Congdon advocates for integrity, consistency, and to diversify your products. The quality of materials should be considered because it affects prices and sets the artist apart from other competition. The price of an item should be the same when selling it in multiple commerce platforms so the product is the same price online, in a store or at an art fair booth. Also, consider selling reproductions of authentic artwork along with the original version such as cell phone cases, coffee cups, clothing, journals and gicleés. However, Towse (1996) believes labor and costs should influence the price of products instead of the intrinsic value of an artwork. Often artists neglect to consider the time invested in research, planning, acquiring supplies, the costs for supplies and studio space. He implores artists to track the hours and costs associated with each projects. Furthermore, Towse encourages artists to secure copyrights for their work for the purpose of intellectual property rights and royalties.

Black Sheep of Society

Unwarranted clichés often put labels on people, or categorized them into boxes to make it easier for an individual or a group to make sense about others without having to invest much in. Much of society define artists as black sheep with offbeat personalities, and assumes that in ordered to be blessed with the creative gene artists must be: only dressed in dark or bright colors, freakish and tortured souls, perfectionists or messy, brooding and moody, kooky and eccentric, hippy and bohemian, rich or poor, and the list goes on. However, the reality is art is limitless so why would visionary people be confined by clichés? Creativity is the spark in all of us whether if it is in a grandmother crocheting baby booties, a kindergartner experimenting with finger paint, the economics major in an art studio, an art teacher preparing lesson plans, the stay-at-home-parent who throws ceramic cups while the children are napping, the jock sketching between practices, a daughter using mud to paint on construction paper, the son who builds imaginary worlds out of Legos without instructions, the mechanical engineer creating a prototype for a propulsion engine, and so on. We are all uniquely creative and this gift colors our lives in different hues and shades.

Creative Conclusions

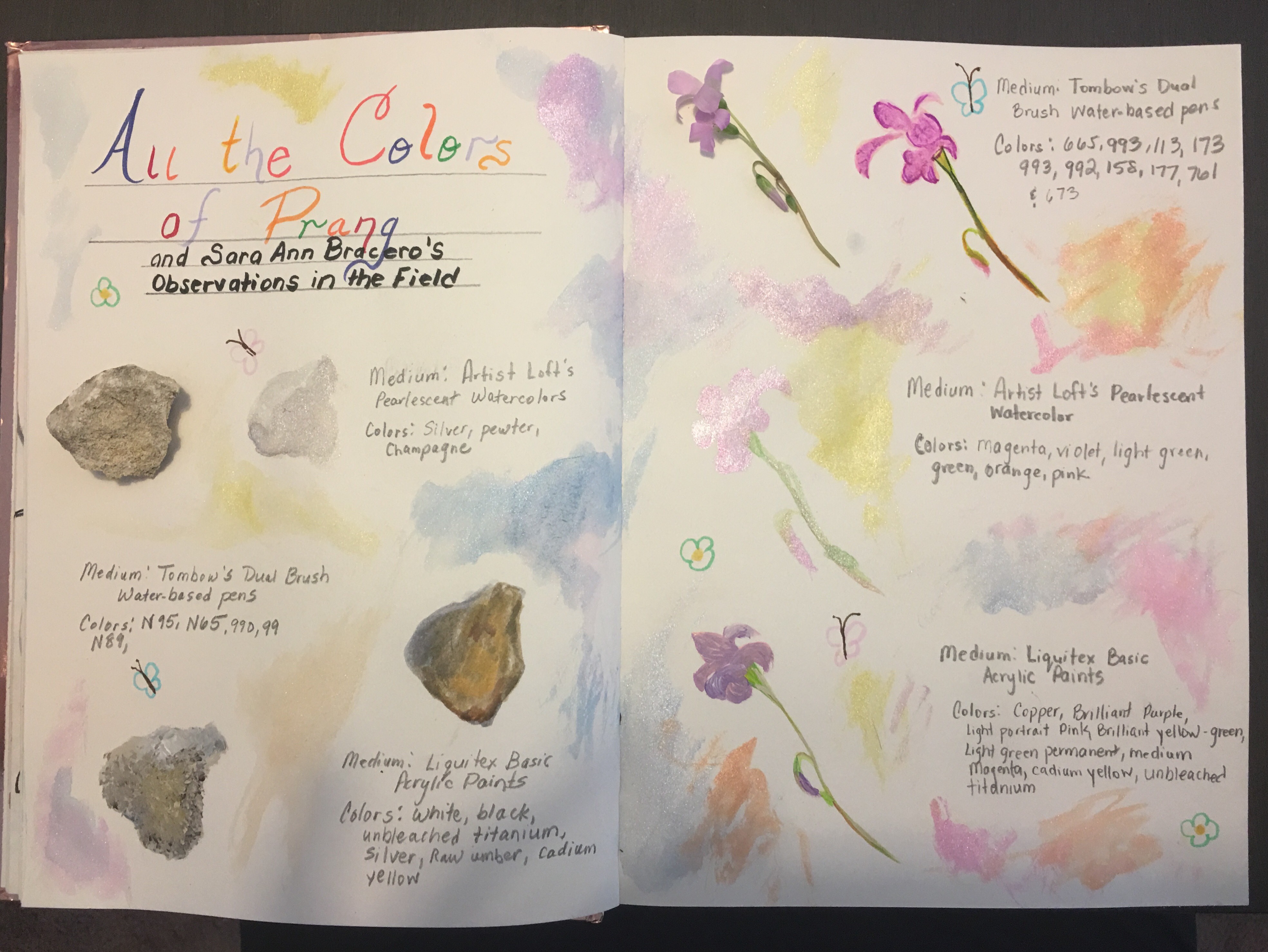

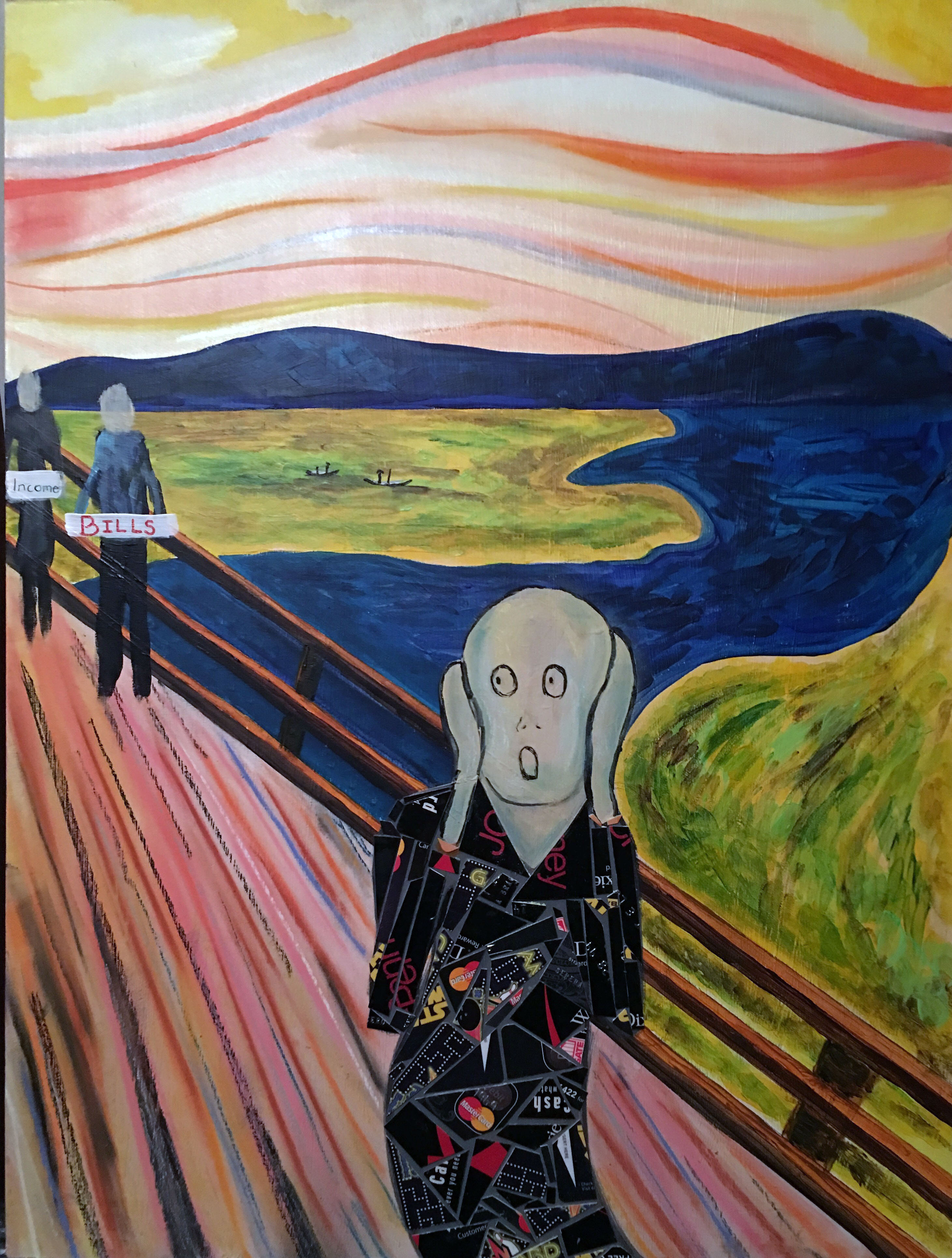

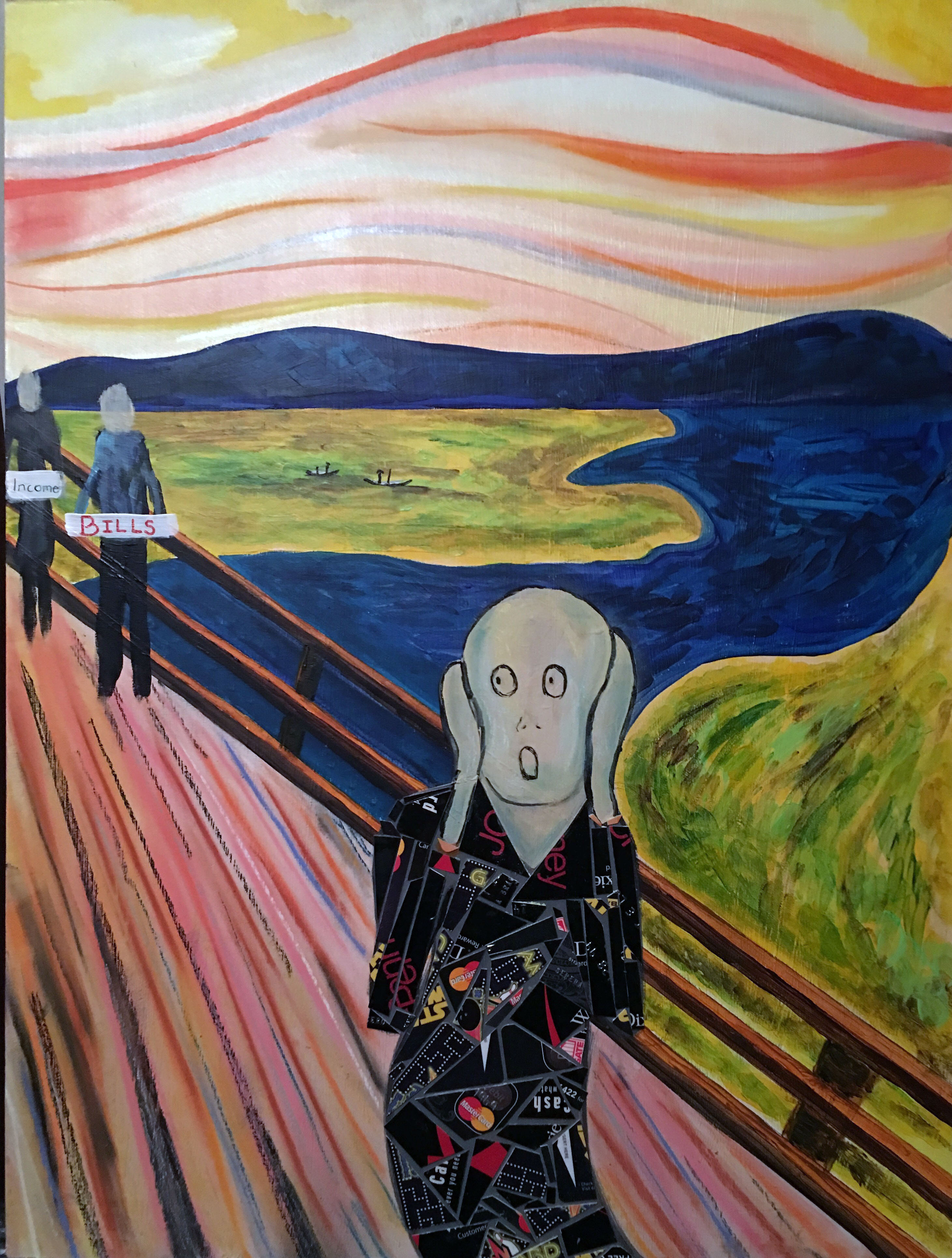

Title: The Modern-Day Scream Medium: Mixed Media on wood panel Size: 18×24″

Title: Glow Up Medium: Mixed Media on wood panel Size: 36×24″

This independent project really helped broaden my understand of myself as an art educator by considering gaps in art education from my own experiences growing up, dealing with negative stereotypes as an artist, finding my own style through experimenting with mixed media and wood panel, and being an artistic daredevil breaking down my own mental blocks in creativity. For the artwork component of the assignment, I chose to create a diptych to compare and contrast the negative and positive perspective of lives of the “starving artist” and the “self-actualized” artist. I decided to heavily experiment with mixed media instead of dabbling with it, so I wanted to really push the envelope. The innate sense of wonder is one of the many key attributes that are found in all of us artists because it ignites creativity and change. Furthermore, I opted to bring techniques already incorporate with much of my artwork, which includes utilizing modern items that are necessities of everyday life to create textures for the purpose of highlighting contemporary issues in society, accentuating artwork, and the inclusion of hidden meanings. I enjoy creating new ways for spectators to feel drawn into each piece and evoke the their desire to touch these works because of the realistic and three-dimensional aspect. Additionally, I chose to join found objects with mixed media to capture the freedom and power of creation by combining different techniques, mediums, and styles. The first portion of the diptych is my rendition of Munch’s The Scream(1893). It is a demonstrative piece influenced by the German Expressionism style and denotes isolation, apprehension and stress. I selected this artwork as a point of reference because it is so emotionally charged with similar feelings that anyone can feel when faced with present-day matters such as consumerism, the rising cost-of-living, low-paying jobs, finding alternative ways to generate income or relying on debts in order to make ends meet. My artwork, The Modern-Day Scream, implies the idea of the “starving artist” because the subject is clothed in pieces of cut up credit cards, and is worried about the two secondary people in the distance. These two individuals hold signs stating income and bills. The “income” board is smaller to represent the shortage in pay while the “bills” poster is larger to show the disparity between the two. This piece embodies struggles anyone can relate to in the face of monetary issues, numerous debts and feeling anxious over trying to survive in a society where it now requires two people to work in order to support their family. The second part of the diptych focuses on what I personally perceive to be success. The artwork focuses on what the artist personally perceives as her success in spite of family members and others being unsupportive, and the negative stereotypes of the trite and old notion of the “starving artist” she heard as she grew up. She dispels this idea by believing in herself and focusing on her purpose on earth, which is to make it prettier, colorful, and a safer place for all to enjoy. The theme reinforces living authentically and unapologetically raw through empowerment, connection with the world, and channeling positive energy energy through the delicate balance of fragility and strength. She opens up her colorful soul by sharing her inner world and heart with the outside world through understanding, nurturing and growth. Repurposing miniature coffee creamer cups highlights global issues and implies the importance of upcycling materials to reduce waste in our lives. The beads around the sunflower represent the seeds of creativity spreading throughout the world. The incorporation of different materials for texture embraces the many disciplines of art, and demonstrates the multifaceted lives of all artists. Art is limitless and creativity is the spark in all of us whether if it is a grandmother who crochets baby booties, a kindergartner experimenting with finger paint, the college student in the studio, an art teacher preparing curricula, the stay-at-home-parent who throws ceramic cups while the children are napping, the jock who sketches between practices… we are all lit up by art.

The premise of the paper tackles different stereotypes, provides context and tips to help build a strong business foundation for artists, allayed negative clichés to make a better understanding of how diverse artists are, and proposed ideas to build an art entrepreneurship educational program. Personally, I would like to work with The University of Florida, Warrington College of Business and College of the Arts, to build an Art Entrepreneurship Art Education [AEAE or (AE)2] curriculum for integration into high school art classes to help students be fearless in pursuing their dreams of being artists, help create a larger landscape of creative prosperity for all artists, and improve opportunities for leadership in the arts. The curriculum can be tested in advanced placement art classes or magnet schools to collect data on the psychological aspects of purpose-driven artists, whether if the respondents feel supported in their pursuits, initial expectations of what an art entrepreneur means to the participants, and an exit interview to see if the expectations changed. My idea of an art entrepreneurship program for high schools would focus on teaching students the importance of dedication to studio time, accountability for producing high quality artwork, entrepreneurship, marketing and leadership. At the end of the year, the program would culminate with a scholastic art fair targeting faculty, fellow students, parents, and local community. Each student would be responsible for the following:

- produce a minimum of 15-20 pieces for retail

- create a business plan including a marketing segment dedicated to logo and business card design, fliers, social media management and a mock radio spot/newspaper ad

- booth design and execution

- journal/ sketchbook submittal to document the experience

Along with gaining experience and earning credit towards graduation, I think this would be an amazing opportunity to show students, administrators, and parents the possibilities and importance of an art education. This experience would help students interested in pursuing a college degree stand apart from other applicants. Furthermore, the conducted research can garner support for further funding of the arts, and prepare budding artists to be successful dignitaries in the art industry.

References

D’Errico, C. (2019). Camilla d’Errico. Retrieved from http://www.camilladerrico.com

Cameron, J. (2002). The artist’s way: A spiritual path to higher creativity. New York, New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc.

Congdon, L. (2014). Art Inc. The essential guide of building your career as an artist. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books LLC.

Freeman- Zachery, R. (2007). Living the creative life: Ideas and Inspiration from working artists. Cincinatti, Ohio: North Lights Books.

Grant, D. (2002). How to grow as an artist. New York, New York: Allworth Press.

Casnocha, B. & Hoffman, R. (2012). The start-up of you. New York, New York: Crown Publishing Group.

Kinkade, T. (2019). Thomas Kinkade Studios. Retrieved from https://thomaskinkade.com

Munch, E. (2017), The Scream [Oil, tempera, pastel and crayon on cardboard]. National Gallery, Oslo, Norway. Strickland, C., The annotated Mona Lisa: A crash course in art history from prehistoric to the present. (p.123) Kansas City, Missouri: Andrews McMeel Publishing. (1893).

Reilly, K. (2018, August 3). When schools get creative. Time, 87, 82-87.

Strickland, C. (2017). The annotated Mona Lisa: A crash course in art history from prehistoric to the present. Kansas City, Missouri: Andrews McMeel Publishing.

Solomon. L. (2019). Lisa Solomon. Retrieved from http://www.lisasolomon.com

Towse, R. (1996). Market value and artists’ earnings. In A. Klamer (Eds.), The value of culture: On the relationship between economics an arts. Amsterdam, Netherlands: University Press, pp. 96-107.

Vidot, J. & Be’Nguyen, O. (2016). Fiyabomb. Retrieved from http://www.fiyabomb.com

Copyright © 2010-2025. The Art of Sara Ann Bracero, LLC. All Rights Reserved.